Conservation of the golden-headed

lion tamarin in a changing climate

Copyright Zoo Antwerpen

Copyright Zoo Antwerpen

The golden-headed lion tamarin is an endangered primate species found only in the south of the Brazilian state of Bahia in the Atlantic Forest, a region that has been identified as an important biodiversity hotspot. This small tree-dwelling primate lives in a variety of habitats, from mature and secondary forest to shade-grown cacao plantations.

The golden-headed lion tamarin plays an important role in dispersing the seeds of many fruits and air plants. This contributes to the natural regeneration of the coastal rainforest, making it essential to protect the species and the landscape in which it lives.

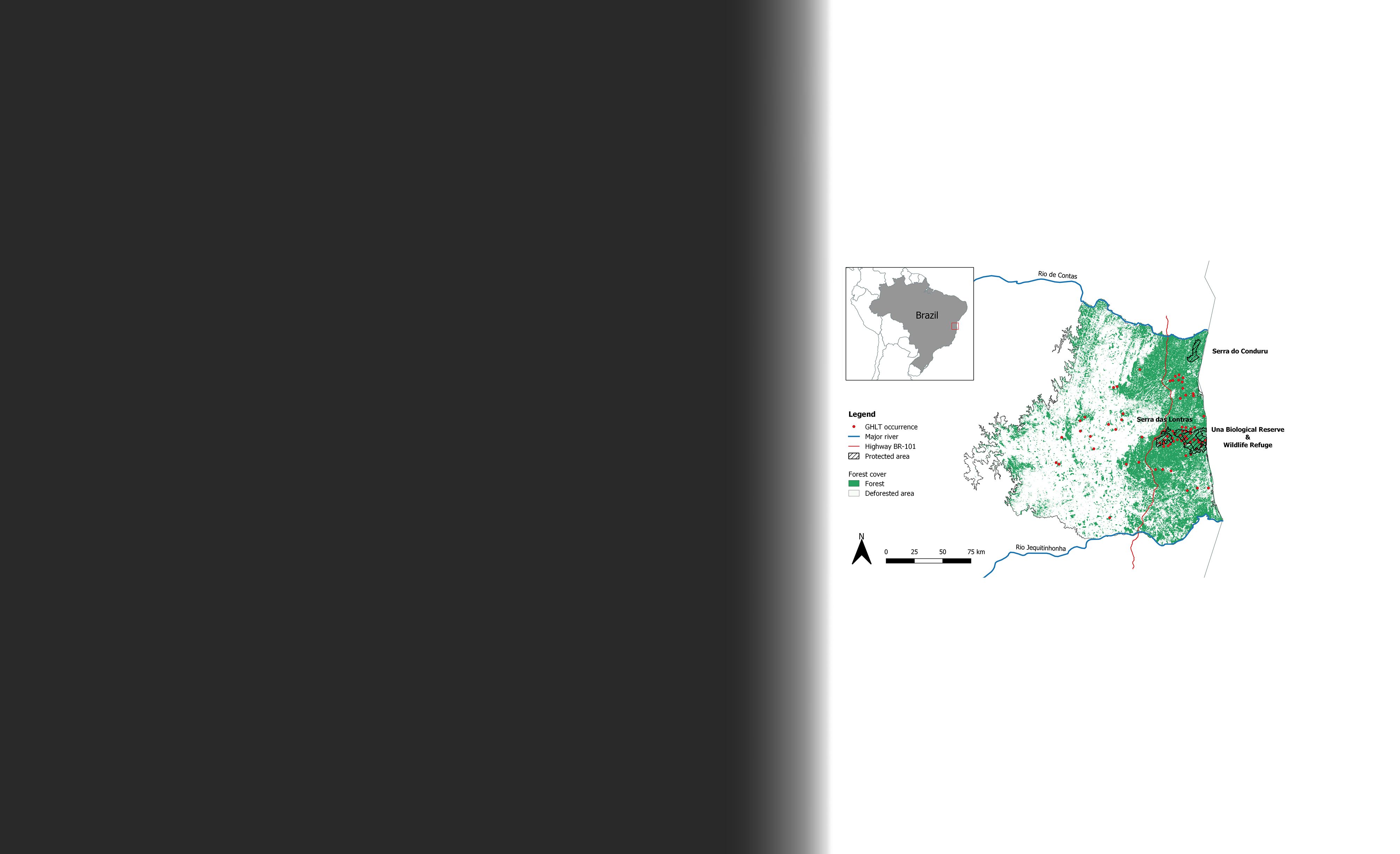

The habitat of the golden-headed lion tamarin is limited in the south of Bahia in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, which has been identified as an important biodiversity hotspot. Credit: Antwerp Zoo CRC.

The habitat of the golden-headed lion tamarin is limited in the south of Bahia in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, which has been identified as an important biodiversity hotspot. Credit: Antwerp Zoo CRC.

Since 2002, the Antwerp Zoo Centre for Research and Conservation (Antwerp Zoo CRC) runs the long-term conservation research project BioBrasil, which focuses on gaining a better understanding of factors that impact the survival, behaviour and demography of golden-headed lion tamarins in fragmented forests.

Brazil's Atlantic Forest once extended continuously along the country’s eastern coastline. But centuries of deforestation for timber, intensive agriculture and cattle ranching, followed by rapid urbanisation, have reduced much of the golden-headed lion tamarin’s habitat to small and isolated patches of forest.

Most of their remaining habitat is unprotected. The pressure to extend agricultural land is high, putting the species at risk from even more habitat destruction.

In the eastern part of the golden-headed lion tamarin’s distribution area in South-Bahia, patches of forest are interspersed with shade-grown cacao plantations, locally known as cabrucas. In these plantations, native large trees are left standing to provide shade to cocoa, and golden-headed lion tamarins can still use these plantations to move between forest patches.

By contrast, in the western part of the species' distribution range, remaining patches of forest are small and isolated by large areas of cattle pasture.

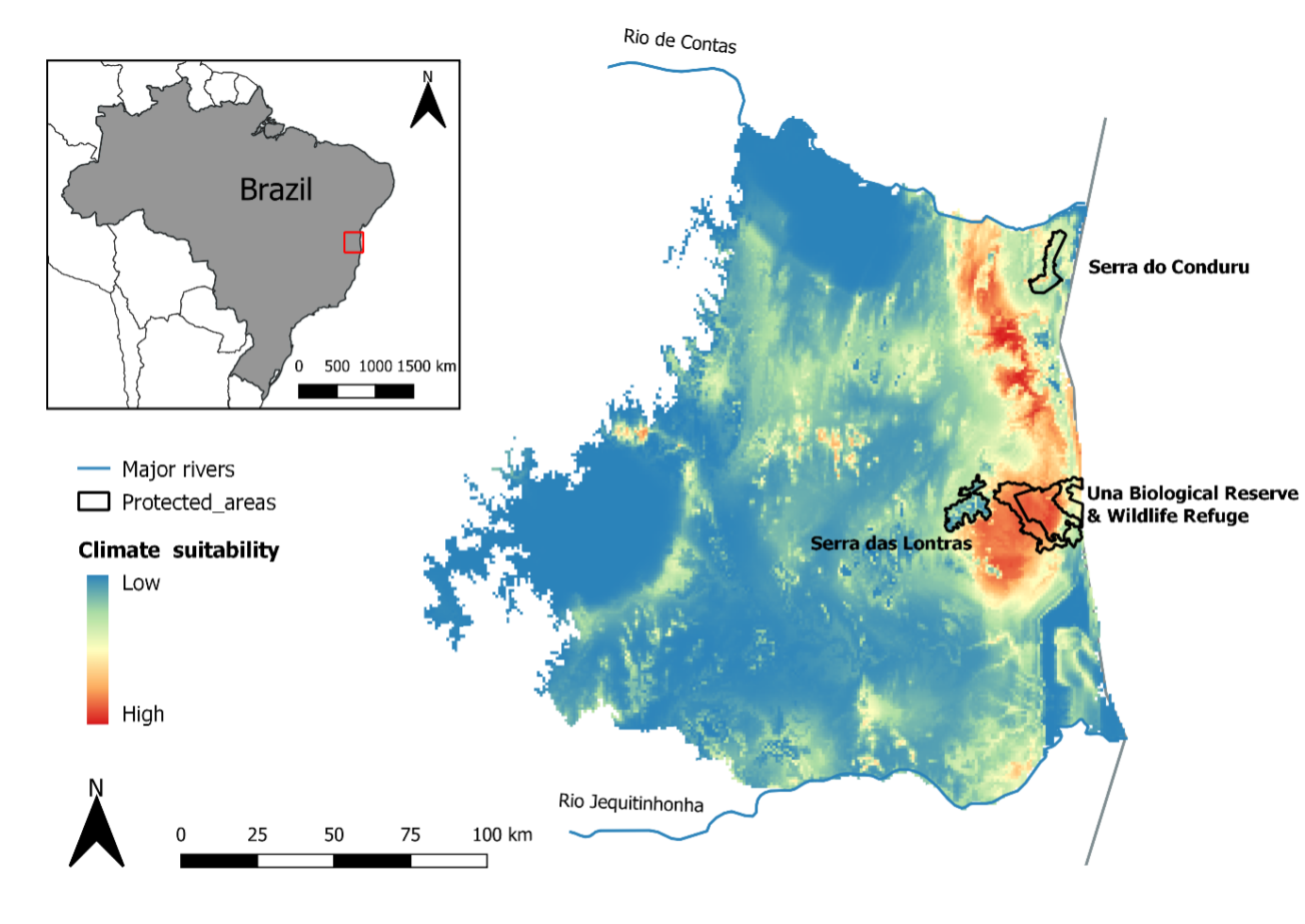

In the east, several protected areas have been established, including Una Biological Reserve and Wildlife Refuge, and Serra das Lontras National Park. They are the only protected areas where you can observe golden-headed lion tamarins in the wild.

Map to the right: The distribution area of the golden-headed lion tamarin in South-Bahia, Brazil. In the eastern part, patches of forest are interspersed with shade-grown cocoa plantations and protected areas have been established. Credit: Antwerp Zoo CRC (based on data from Guy et al. 2016).

Copyright Zoo Antwerpen/Jonas Verhulst

Copyright Zoo Antwerpen/Jonas Verhulst

Climate change is one of the biggest threats to global biodiversity in the 21st century. Many species are likely to shift their distributions in response to changes in their environment. Some may even be at a higher risk of extinction if temperatures continue to rise.

Climate change might also jeopardise the future of golden headed lion tamarins in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest. Yet, how vulnerable these curious creatures are to climate change remains unclear. By analysing, mapping and communicating any climate-related shifts in their distribution, cost-effective conservation strategies and actions can be developed.

Investigating which regions will still have a suitable climate in the future

Supported by the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), researchers from the Flemish Institute for Technological Research (VITO) and the Antwerp Zoo CRC have joined forces to shed light on the impact of climate change on the future distribution of the golden-headed lion tamarin. They are also exploring the effectiveness of existing reserves to protect climatically suitable areas.

Collecting data in the field

For many years, biologists have been collecting direct observations of golden-headed lion tamarin populations during field surveys. Since 2002, the Antwerp Zoo CRC runs the long-term conservation research project BioBrasil, based in south Bahia, which focusses on gaining a better understanding of factors that impact the survival, behaviour and demography of golden-headed lion tamarins in degraded and fragmented forests.

The project team also works with local communities to raise awareness of environmental issues and to improve the development of sustainable forms of land management, reconciling the needs of local communities with the conservation of the species.

Background photo: Copyright BioBrasil/Igor Inforzato

Gaining access to high-quality climate data

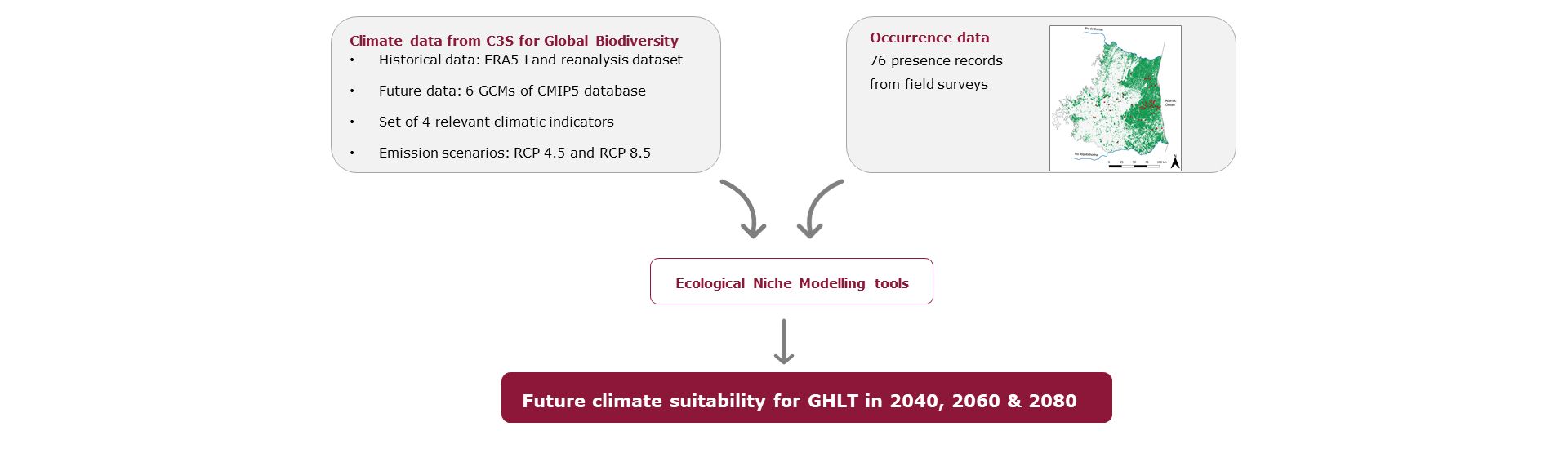

Research institutes such as VITO can use the high quality C3S datasets available for free, for comprehensive processing into tailored climate information products. In a first step, VITO used historical climate data from the ERA5-Land dataset and future climate projections from the CMIP5 dataset to develop two bioclimatic datasets: A dataset of 78 tailored climatic indicators for the past climate and a dataset of 78 tailored climatic indicators for the future climate. The indicators are specifically relevant for applications within the biodiversity and ecosystem services communities. They cover bioclimatic variables characterising surface energy, drought, vegetation sensitivity, marine environments, soil moisture and wind, as well as Essential Climate Variables which describe the Earth’s changing climate, some which are available in C3S.

“The regular production and wall-to-wall coverage provided by the Copernicus Climate Change Service data makes them suitable for our ecosystem accounting tools.”

From the newly developed dataset of 78 tailored climatic indicators, the annual mean temperature of the wettest quarter from 1990 to 2090, was selected as a relevant climate predictor for the golden-headed lion tamarin. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service, ECMWF.

From the newly developed dataset of 78 tailored climatic indicators, the annual mean temperature of the wettest quarter from 1990 to 2090, was selected as a relevant climate predictor for the golden-headed lion tamarin. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service, ECMWF.

Relevant climate predictors for the golden-headed lion tamarin include the annual mean temperature, the mean temperature of the wettest quarter, the precipitation of the coldest quarter, and aridity in the wettest quarter and they were selected by local stakeholders with significant expertise in the conservation of the species.

“To assess how species distributions are changing in response to climate change, we require high-quality data. The C3S Climate Data Store is a valuable resource in this regard”

Supported by C3S, the Antwerp Zoo CRC then combined these tailored climate data with information about golden-headed lion tamarins from field surveys. The result is a modelling tool that maps areas with suitable climates for the tamarin now and in the future.

Field observations of golden-headed lion tamarin populations are combined with tailored climate data from C3S, in Ecological Niche Modelling tools in order to map areas with suitable climates for GHTL. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service, ECMWF.

Field observations of golden-headed lion tamarin populations are combined with tailored climate data from C3S, in Ecological Niche Modelling tools in order to map areas with suitable climates for GHTL. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service, ECMWF.

Is time running out for the golden-headed lion tamarin?

According to the team's projections, over the next 60 years the effects of climate change will dramatically reduce the distribution of the tamarin.

In addition, protected areas are unlikely to remain climatically suitable if the global average temperature increase is not kept well below 2°C.

Current climate suitability of the study area in Bahia forest for the golden-headed lion tamarins. Protected areas are indicated in black. Warmer colours represent areas with a high climate suitability while cooler colours represent areas with low climatic suitability. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service, ECMWF.

Current climate suitability of the study area in Bahia forest for the golden-headed lion tamarins. Protected areas are indicated in black. Warmer colours represent areas with a high climate suitability while cooler colours represent areas with low climatic suitability. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service, ECMWF.

Map of the climate suitability within the golden-headed lion tamarin’s habitat for the future horizons of 2020,2040, 2060 and 2080 under RCP4.5. Warmer colours represent areas with a climate more suitable for the tamarin, while cooler colours represent areas with lower climatic suitability. Protected areas are indicated in black. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service, ECMWF.

Map of the climate suitability within the golden-headed lion tamarin’s habitat for the future horizons of 2020,2040, 2060 and 2080 under RCP4.5. Warmer colours represent areas with a climate more suitable for the tamarin, while cooler colours represent areas with lower climatic suitability. Protected areas are indicated in black. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service, ECMWF.

Under the future climate change scenario of RCP 4.5, the maps show that a narrow strip of suitable area would still remain for the tamarin in 2040. This means that protected areas might still be able to provide some refuge. Unfortunately, by 2060 there would likely be very little suitable land left for the tamarins to live on.

“Knowing which regions will have the highest climate suitability is essential for the conservation planning of this flagship species that is key to its forest habitat, and hence climate change mitigation”

Ours to save

If we do not succeed in keeping global average temperature rise well below 2°C, the golden-headed lion tamarin and many other species could face extinction by the end of the century.

How can this service help save the

golden-headed lion tamarin?

This case study provided a first insight into the potential effects of climate change on the distribution of this endangered tamarin. Such information is valuable for local stakeholders involved in conservation efforts.

The final outcomes will be integrated into a strategic conservation action plan, put together by the Bahian Lion Tamarin Conservation Initiative. The aim is to ensure the long-term viability of wild populations of golden-headed lion tamarins through science-based planning and action. It will involve many different stakeholders – from landowners and local producers to scientists and protected-area managers.

The information from this case study will support the development of conservation strategies that focus on landscape management. These strategies will improve the connectivity and protection of valuable areas to help the species adapt to climate change.

Looking to the future: Combatting loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services

SDG 15: Life on land

Nature is critical to our survival. It provides us with oxygen and food, but also regulates our weather and pollinates our crops. But human activity has already altered almost 75% of Earth’s surface, leaving little room for wildlife and presenting us with a biodiversity crisis.

SDG 15 is devoted to “protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss”.

By developing a dataset and tool that can be used to investigate the impact of climate change on the future distribution of the golden-headed lion tamarin and other animals, this case study contributes to protecting and restoring life on land.

SDG 13: Climate action

2010–2019 was the warmest decade on record. As greenhouse gases continue to be released, the UN is calling for urgent action to reduce the harmful effects of climate change. This includes integrating climate change measures into national policy frameworks.

This case study is helping the biodiversity and ecosystem services communities assess the potential impacts of climate change, which will help them prepare for a new future. It will also provide evidence for those communicating about climate change.